Foster Care

Can the system handle soaring demand?

By Kay Nolan, July 20, 2018

Increasing demand for foster care and adoption services is overwhelming state and private child-placement agencies across the country, a trend stemming largely from parental opioid abuse that has shattered families and orphaned thousands of children.

Overworked caseworkers are boarding children in hotels, state offices and even cars while they scramble to find homes for them, even as many states cut spending on programs that benefit children and families.

Meanwhile, many child welfare caseworkers and foster parents are leaving the system, citing work-related stress and the strains of caring for young victims of abuse or neglect.

Some child welfare experts see hope in a new federal law that prioritizes programs aimed at keeping families together, but others worry the law will divert resources from foster care services for children with behavioral

problems.

At the same time, some tax-supported, faith-based child welfare agencies have refused to place children with prospective LGBT foster or adoptive parents, igniting a bitter cultural debate and legal battles over religious rights.

Rebeka Romero hugs her sons Joseph, 8, left, and Travis, 10, after finalizing their adoptions on Nov. 16, 2017, in Denver. Romero and her husband initially raised the boys — along with their sister, Lilly — as foster children. Some child welfare advocates worry that a federal law enacted in February will divert resources from programs designed to

find adoptive families for foster children.

Shannon Smith, left, and his husband, Ross Stencil, pose with their adopted sons, Giovanny (front left)

and Louis, in West Hartford, Conn., on May 17, 2018, the same day Connecticut child welfare officials

announced a campaign to recruit LGBT peopleto serve as foster or adoptive parents.

THE ISSUES

Drug abuse, poverty and declining resources have created a crisis for foster care agencies, child welfare officials say, with the impact felt in states

throughout the country:

- In Florida last February, as many as a dozen foster children were forced to live in cars in a gas station parking lot because their caseworkers could not find beds for them.

- In Pennsylvania, state officials desperate to find new foster families began running public service ads on TV in March, the first such recruitment drive in a decade.

- In Indiana, the number of children in foster care has more than doubled since 2014, largely because of parental opioid addiction, officials say

“It has just exploded our systems,” said Judge Marilyn Moores, who presides over juvenile court in Marion County, which includes Indianapolis, the state’s largest city.

A major factor, child advocates say, is a nationwide epidemic of opioid addiction that is destroying families and overwhelming foster care systems, even as many states cut spending on programs that benefit children and

families. About 92,000 children were removed from their homes in fiscal

2016 because parents were abusing opioids or other drugs, according to

the most recent federal figures.

Meanwhile, in at least half of thestates, the number of foster homes fell

between 2012 and 2017, according to the Chronicle for Social Change, an

online news source that works to improve child welfare services. Twenty states managed to add foster beds, but in 11, the increase in the number

of foster children far outstripped the expanded supply.

“Most states already face a big gap between the number of children who need families and foster homes ready to receive them,” said Jedd Medefind,

president of the Christian Alliance for Orphans in McLean, Va., which works to improve foster care and adoption services.

“The opioid crisis is widening the gulf further still.” A new federal law — the Family First Prevention Services Act — is expected to remake the nation’s foster care system. Passed in February, the law allows states, for the first time, to tap federal foster care dollars to help struggling parents at risk of losing custody of their children. The law’s backers say it will make foster care less necessary, but critics worry it will increase the demand for foster and adoptive families while diverting resources from efforts to recruit and retain them.

Further complicating the picture, cultural conflicts have emerged in some states over refusals by publicly funded faith-based foster care and

adoption groups to place children with LGBT couples.

The Trump administration’s discontinued practice of separating undocumented immigrant families also has strained foster care resources, say child welfare advocates, with thousands of migrant children taken from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border from April to June ending up in foster homes and shelters

across the country.

“They’re crippling an already overwhelmed system,” said Michelle Brané, director of migrant rights and justice at the Women’s Refugee Commission, a New York City organization that works to help women and children victimized by conflict.

Child welfare agencies also have had to find homes in recent years for hundreds of thousands of unaccompanied children who crossed the Southwest

border without permission or who were left stranded in the United States after their parents were deported for entering the country illegally

The nation’s foster care system includes state agencies, nonprofits

and private for-profit contractors who provide temporary homes to children

whose parents are unable, unfit, unwilling or unavailable to care for them.

A federal agency — the Children’s Bureau in the Department of Health

and Human Services — reimburses states for some of the costs of providing foster care and adoption assistance for children. The bureau spent about

$8 billion in fiscal 2017.

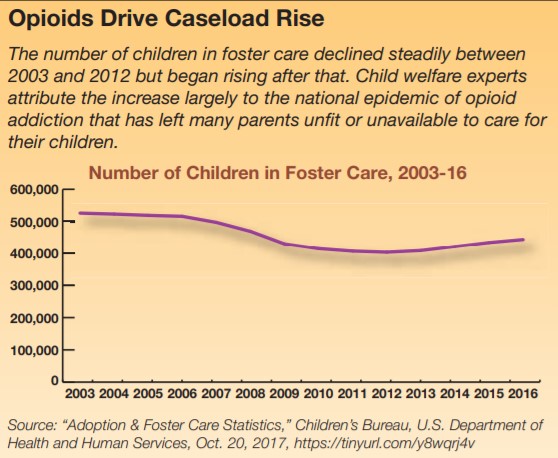

The number of children in foster care peaked at 567,000 in 1999, then

dropped steadily through fiscal 2012, according to federal statistics. By fiscal

2016, it had increased 10.2 percent — from 397,000 to 437,500. (See graphic,

above.) While official numbers are not available for 2017 and 2018, researchers estimate that about 500,000 children are in foster care today.

“It’s pretty much every state . . . that [has] seen an increase in the number of children in foster care,” said John Sciamanna, vice president of public policy at the Child Welfare League of America, a coalition of public and private agencies in Washington that

serves vulnerable children and families. “What you are seeing now is just a

straining of the system.”

And in many states, foster care numbers have surged in recent years because officials have created hotlines that urge the public to report possible cases of abuse or neglect.

In some states, legislators have cut programs that help the poor, leading to more cases of child abuse and neglect, and boosting the number of children

in foster care, experts say. In Arizona, for example, the five ZIP codes where children are most likely to be removed from their homes and placed in foster

care all have high poverty rates.

State budget cuts also have added to problems facing child welfare agencies, which rely partly on state funding to reimburse foster parents’ expenses and recruit new foster and adoptive families, according to a May report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the investigative arm of Congress.

Recruiting minority adoptive families is particularly difficult, which helps explain why African-American children spend more time in foster care than

others, researchers say. Black children are placed in foster care about twice as often as white children, are more likely to be moved often among placement settings and are less likely to be placed with relatives, according to John H. Laub, a University of Maryland criminology professor, and Ron Haskins, co-director of the Center on Children and Families at the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank.

“Racial inequality touches every aspect of the foster care system,” the two wrote in a recent policy paper. Opioid addiction is among the most difficult challenges facing the nation’s child welfare agencies, experts say. Social workers increasingly must find temporary homes for the children of addicted

parents, and thousands of children have been orphaned by opioid overdoses.

A study by the University of South Florida’s College of Public Health found that for every additional 6.7 opioid prescriptions written per 100 people, the rate

that children were removed from homes due to parental neglect rose 32 percent. Indiana, Florida, Georgia and West Virginia — each of which has a high rate

of opioid abuse — were among states with the largest increases in foster children between 2015 and 2016.

Many child welfare experts say the damage that parental drug addiction inflicts on families justifies removing children from those homes. But others say adults who abuse drugs are not necessarily bad parents, and separating families is so traumatic for children that child welfare agencies should keep families intact while ensuring that the parents receive drug treatment.

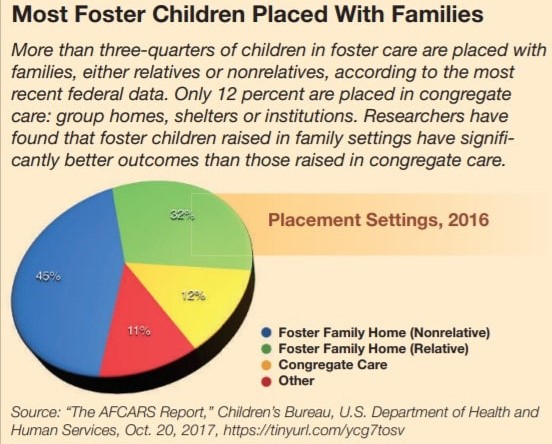

Foster care is supposed to be temporary: The system’s ultimate goal is to reunite foster children with their birth parents or arrange for them to be adopted. But about 118,000 foster children were awaiting adoption in fiscal 2016 because they were too young to leave foster care and could not reunite with their birth families, according to the latest federal data. About half of the children who left foster care that year were reunited with their families, and 23 percent were adopted.

Some child welfare advocates view LGBT couples as a crucial foster care resource. Research shows that samesex couples are much more likely than

heterosexual couples to become foster or adoptive parents. “The last decade

has seen a sharp rise in the number of lesbians and gay men forming their

own families through adoption, foster care, artificial insemination and other

means,” according to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

But some states have enacted “religious liberty” laws allowing publicly supported faith-based foster care and adoption groups to refuse to place children with same-sex couples. Supporters of the laws note that some faith-based groups have stopped offering foster services rather than serve LGBT families and say states need as many foster care and adoption providers as possible. Critics of the laws say they amount to state sanctioned discrimination.

Good caseworkers are crucial to the foster care system, but work-related

stress is causing many to seek other jobs. An estimated 20-40 percent of caseworkers quit each year, double the 10-12 percent rate considered optimal, according to Casey Family Programs in Seattle, which consults with child welfare systems throughout the country.

“I have personally cried at work,” said Rosanne Scott, a caseworker in Oregon’s child welfare system. “It’s a very high-stress job.”

Foster parents face their own pressures, with about half quitting within the first year, according to child advocates. Irene Clements, executive director of the National Foster Parent Association in Pflugerville, Texas, blames a “lack of support, poor communication with caseworkers, insufficient training to address a child’s needs and the lack of asay in the child’s well-being.”

Such complaints can be particularly common among foster parents raising severely traumatized children with serious behavioral problems. (See sidebar)

In some cases, limited placement options for foster children and poor agency management practices have endangered children’s safety. In Oregon, for example, caseworkers unable to find homes for foster children have housed them in hotels and state offices, leading to reports of abuse and neglect, according to an audit released last January by Oregon’s secretary of state. It called the state’s child welfare system “disorganized, inconsistent and high risk for the children it serves.”

A 1997 federal law requires states to quickly reunite foster children with their birth parents or find a family to adopt them. But many foster children come of

age without finding permanency, some living in 20 or more homes before turning 18. Research shows that, as young adults, they experience higher rates of homelessness, unemployment and incarceration than other children. In 2016, some 20,500 foster children aged out of the foster care system without a permanent family. (See sidebar)

SailFuture, in St. Petersburg, Fla., takes an innovative approach to teaching troubled foster care teens the social and coping skills they will need as adults. The teenagers spend three-month stretches twice a year on a sailboat, cooking meals on board, cleaning and doing schoolwork under the guidance of adult mentors. The remainder of their time until they reach age 18 is spent in one of two group homes the program operates.

“Our goal is to redesign the system,” says Michael Long, SailFuture’s founder. “The way it is now is a result of people giving up and saying, ‘No matter what we do, these kids can’t be saved, so let’s not put any more energy into trying to do this better.’ We say, ‘This kid isn’t doing bad things because he’s a bad person. Maybe it’s because a lot of people have done bad things to him and he doesn’t know how to grapple with it.’ ”

Overall, foster children are more likely than other children to have developmental and mental health problems, and many experience abuse and neglect while in the care of foster parents or at group homes.

Schylar Baber, executive director of Voice for Adoption, a lobbying group in Washington that advocates for foster children awaiting adoption, lived in between 2000 and 2015, leading juvenile court judge Moores to say, “This isn’t a trickle. This isn’t a wave. It’s a tsunami.”

Nationwide, parental drug abuse accounted for 34 percent of foster care placements in fiscal 2016, up from 32 percent the previous year, the largest percentage-point jump among the 15 factors that led to 11 different foster homes, three group homes and two residential treatment centers while growing up. He says he was abused in some of those settings.

Marilyn Moores, a juvenile court judge in Indianapolis, works amid piles of case files in August 2017. Moores said the number of Indiana children removed from their homes due to parental drug abuse has reached “tsunami” levels.

“The best outcome for children is in a permanent, loving family,” says Baber. “Foster care was never intended to be a long-term solution.”As foster care officials and child welfare advocates debate how to cope with the ongoing crisis, here are some of the questions they are asking:

Do officials remove children too quickly from homes where theparents abuse drugs?

Drug-related foster care cases in Indiana increased more than sixfold children being placed in foster care, according to federal figures.

An investigation by The Hill newspaper in Washington found that the number of children in foster care increased dramatically over the past four years in states where opioid abuse is highest. Those included Alabama (more than 30 percent), Ohio (28 percent) and West Virginia (42 percent).

Child welfare experts agree opioid addiction is straining the nation’s

overburdened foster care system, but they disagree about whether parental

substance abuse always justifies placing children in foster care.

“There is probably no more important dialogue to have in child welfare right now than the one about when children need to be removed from an addicted parent, and when they can be kept safely in the home or with family while treatment is provided,” says John Kelly, senior editor of The Chronicle of Social Change.

Some child advocates say courts and child welfare officials often have no choice but to remove children from homes where the parents are abusing drugs, noting that parental drug abusers frequently relapse, putting children at risk of being removed repeatedly from the same home.

“Children start to miss school,” says Priscilla Brown, supervisor of child protective services in Columbia County, Ga. “They miss doctor and dentist appointments. Parents might use money they’d otherwise spend on food and necessities on drugs.”

Other experts counter that neglect related to drug abuse can be hard to measure, and that substance abuse is often treatable.

Drug addiction is not always a reliable predictor of an individual parent’s behavior, says Dr. Mishka Terplan, a professor in obstetrics and gynecology and an addiction specialist at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Va. “There’s nothing in a [drug] urine test that tells you anything about a woman’s ability to safely and lovingly mother her child,” Terplan says. “Urine drug tests have been used to a large extent as a parenting test, and that’s a completely inappropriate use of urine drug testing.”

Terplan particularly opposes the practice of placing infants in foster care if they or their mothers test positive for opioid use, saying mother-child bonding

is crucial for an infant’s mental health.

Fourteen states and the District of Columbia include newborns’ exposure to drugs or alcohol in their definition of neglect. 25 But Terplan says babies born addicted to opioids can be treated with few or no lasting health effects.